I’m cruising along the 101 in the mid-afternoon, just before rush hour, and the hunger pangs begin. I exit the freeway and take a couple sharp right turns until I find myself in the McDonald’s drive-thru lane. All I’m ordering is one large box of french fries. They’re fresh, made just in time for the dinner rush, and hot enough to burn my fingertips. My favorite is the long, soggy fry that droops from the front row, resting upon the red container’s golden arches. The bag, grease-stained, tells me something new: “this McDonald’s is locally owned and operated.”

This information isn’t a surprise, as most fast food restaurants are franchised, but it raises more questions than answers. Is this message, juxtaposed on top of a yellow illustration of California with a bright red heart overlapping Los Angeles, exclusive to this region of junk food lovers? Of all the industries the Southland is known for — entertainment, oil, avocados — fast food might just be our biggest export.

The first McDonald’s opened in San Bernardino, and is just one of many chains that have emerged from Southern California. Taco Bell fried up tortillas in Downey, Baskin Robbins scooped their 31 flavors in Pasadena, In-n-Out perfected their animal sauce in Baldwin Park, Carl’s Jr. tucked into a tiny burger stand in Los Angeles, and Wienerschnitzel served chili dogs in Wilmington. Just outside of LA County, Del Taco conquered the Mojave in Yermo and Jack in the Box won over San Diego.

According to McDonald’s own website, about 93% of their locations are franchised by whom the company describes as “independent local business owners.” The biggest restaurant chain in the world wants you to believe that it’s run by mom and pop businesses, but the reality is that most of the franchises are run by large restaurant groups like Retzer Resources, which owns 103 franchises across 5 states in the Deep South.

I tried to find the owners of the three McDonald’s in my regular rotation, but this information is opaque. Property records show the registrant as McDonald’s Corporation, which was already a give in. With some digging, I learned that the McDonald’s in my neighborhood is #1922. I can find that they’re owned by Henrose Corporation through public filings of worker’s compensation lawsuits. From there, I locate the owner’s name, his Facebook page, and his father’s obituary. I read in the obit that the family has run this McDonald’s since 1971. But discovering this information feels unsavory. If McDonald’s had wanted me to know who owned it, it would have been proudly displayed somewhere.

I find it strange that McDonald’s wants to appear like a local business, but won’t readily divulge any information about their franchise operators. In my Los Angeles neighborhood, the business owners like to mix with the community, and I’ve built relationships with many of the places I frequent. I once was a dog sitter for a burly bulldog that loved to snuggle; she belonged to the owner of an ice cream shop down the block. I worked with the owner of the zine library around the corner to set up drawing workshops, and before he moved in, I had volunteered for a different artist-run space that occupied the space. When the owner of my favorite coffee shop passed away, I added a small trinket to the memorial that appeared in front of the business.

In Los Angeles, there’s only a handful of public McDonald’s owners. Two sisters in Inglewood own an empire of 18 McDonald’s, and they’re often touted as a success story for aspiring franchisers to emulate. They took over their restaurants when their mother, Patricia Williams, retired, and have attracted headlines from the LA Times, Blavity, and our local CBS and NBC affiliates. McDonald’s has even made a hybrid documentary-advertisement about their single mother who poured her savings into her first franchise. But the corporation hails their heartwarming story because these women are the exception to the rule.

McDonald’s emphasis on local ownership is just another version of “smallwashing,” a term Grub Street writer Emily Sundberg used to describe brands that position themselves as small businesses even though they’ve fundraised millions through venture capitalists. In a city like Los Angeles, where the stereotypical diner is prioritizing the farmer’s market, McDonald’s knows that eschewing their corporate persona might make people feel better about supporting a company that actively lobbies against raising the minimum wage, has violated child labor laws, and has pioneered unhealthy, addictive diets for vulnerable people in food deserts.

Generally, people love when brands acknowledge their humble origins, especially if they’re shared with the consumer. We see this often with celebrities; I love Vince Vaughn simply because he spent some years in my hometown, Buffalo Grove, IL. For both brands and A-Listers, a regional connection suggests that the company, cultivated in the same environment that raised us, holds the same values and traditions as the customer.

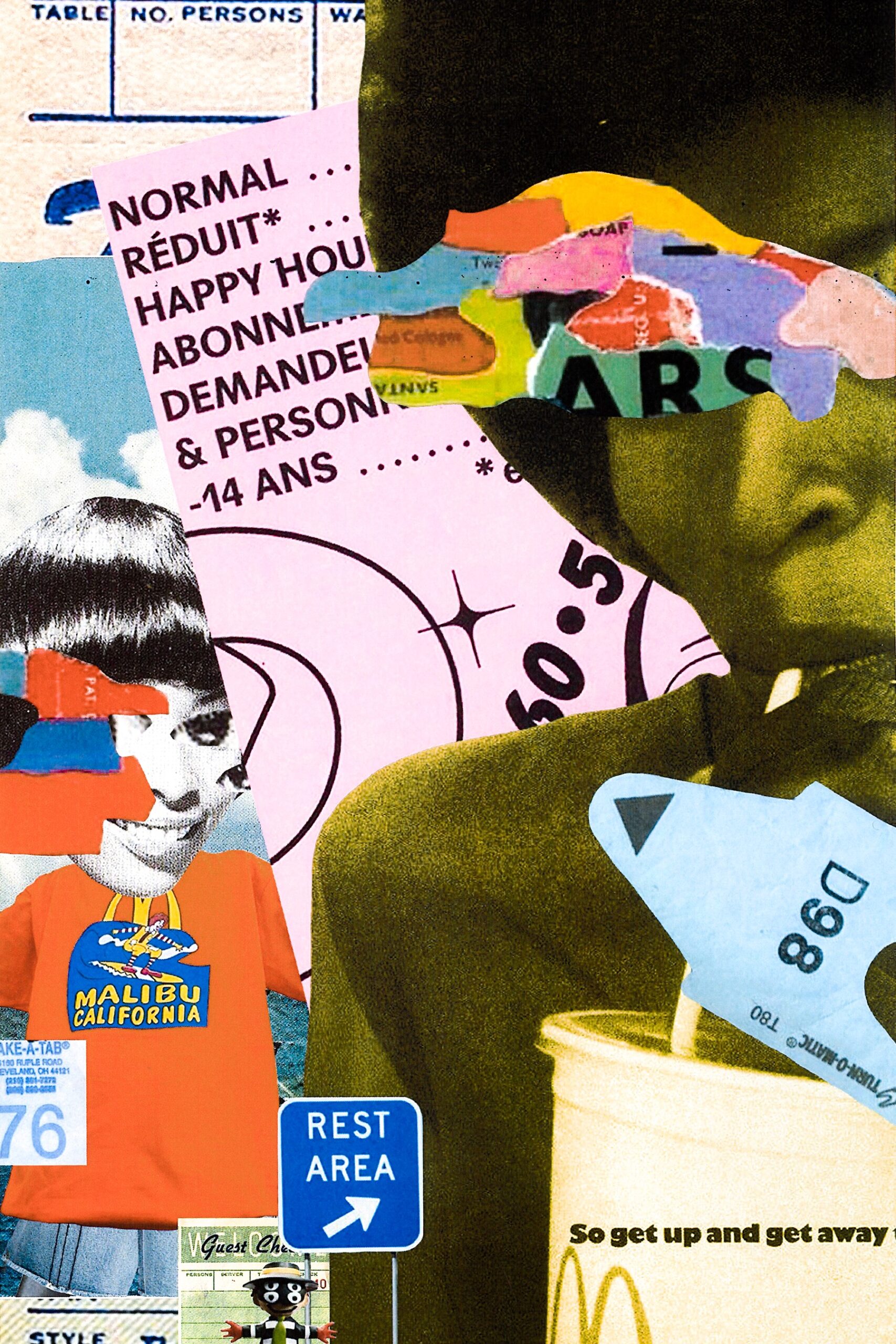

Californians especially love to showcase their pride for their favorite fast food chain. As a diehard McDonald’s fan, one of my most prized possessions is a t-shirt with Ronald McDonald surfing a large wave in front of the golden arches. I impulsively bought it from the drive-thru on the famed Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu. As I crawled to the cashier’s window, craving late night fries after teaching a four-hour studio, I saw the custom shirts through the cashier’s glass box paired with a handwritten sign charging $20 apiece. It was handed to me alongside my brown bag, another branded with “this McDonald’s is locally owned and operated.”

With little research, I can find my treasured Malibu McDonald’s shirt online, but on Grailed it’s described as “vintage” and “rare.” There’s a knock off on AliExpress that’s half the price, and somehow the design is a more polished, vectorized version of the illustration. With its freehand design, the name of an iconic tourist destination, and the absurdity of a corporate tie-in, the Malibu McDonald’s t-shirt has the right level of kitsch and brand recognition to make the perfect souvenir and a viral sensation. Knowing that it’s not rare — even though they’re only plentiful due to theft — dampens the luster of owning a collectible McDonald’s tee.

The market for Californian fast food swag is potentially enormous. Though there aren’t any concrete numbers on revenue from merchandise sales, Taco Bell has a robust online store and has found it worthwhile to collab with Forever 21 and launch a pop up hotel in Palm Springs, which sold out in minutes. In-n-Out, understanding its cult following, sells its famous palm tree design, which encircles its paper cups, as tube socks. I’ve seen these in person, paired with checkered Vans, worn by a hype kid skateboarding past me.

My dad, a Chicagoan who craves a monster taco whenever he’s west of the Mississippi, had the clown head of Jack, CEO of Jack-in-the-Box, bobbing on his minivan until it disappeared one day, potentially stolen by another fan. His enthusiasm for the brand demonstrates that fast food loyalty reaches far across California’s borders. eBay is a treasure trove of fast food collectibles, and only hints at the unfathomable amount of merchandise that has been hawked over the years, as well as the world’s hunger for these objects. A quick search of “fast food promotion” produces rarities like the talking Taco Bell chihuahua (may as well splurge on the entire set of nine,) debossed Baskin Robbins ice cream scoops, inflatable Wienerschnitzel UFOs, and Carl’s Jr. cup-shaped magnets that hold pencils instead of straws. It’s important to distinguish these branded items from the usual toys fast food companies give away with kid’s meals, which also dominate online listings, but aren’t as lucrative. While the mania for McDonald’s teenie beanie babies fizzled out in the 90’s, the search for a rare Grimace plush continues, and will set collectors back about 20 bucks.

Some of the rarest fast food souvenirs are the hat and lapel pins, made scarce because they’re only handed out to employees. Franchises use these tokens as rewards for completing mandatory training, to celebrate holidays, or just to show off spirit. Taco Bell, for example, canonized its breakfast crunchwrap-cinnabon-coffee combination in a bulky enamel pin that is much more attractive than any of the $2 buttons hawked on their official store.

McDonald’s, the champion of employee pins, captures the charm of the Malibu McDonald’s t-shirt with their hyper-local flair. My favorites come from moments frozen in time, like the 1984 Olympics, of which McDonald’s was a proud sponsor, or an adorable pin produced for the Oxnard Strawberry festival.

One of the most fascinating finds are pins celebrating McDonald’s opening up at the Crocker Center, now known as the Wells Fargo Tower, in Downtown Los Angeles. An isometric view shows the then-new nondescript skyscrapers in the shadow of the McDonald’s logo. The pins had to be produced between 1983, when the buildings opened, and 1987, before the name was changed to Wells Fargo. While the pin is not as photogenic as Ronald on a surfboard, the simple design and connection to lost local history is more interesting than anything celebrating the annual return of the McRib.

That tie between franchise and place drew me back to the slogan that has been haunting me every time I order fries: “this McDonald’s is locally owned and operated.” Every McDonald’s I regularly visit provides bags and cups with this message printed on them. Eventually, I found that it is not exclusive to the state that birthed McDonald’s. Oklahoma and Tennessee franchises replicate the design, replacing the bold image of California with their own borders.

Now I see one slogan with two completely different messages. One makes consumers believe that they’re shopping small and supporting their community. The other is McDonald’s speaking to itself, acknowledging the local franchise owners that have helped their restaurant take over the world. It is not possible to be the mom and pop business and the corporate behemoth all at once.

But I still can’t get enough of those fries. I thank the drive-thru attendant for her service and as I drive home, I stuff a fistful of hot fries into my mouth while muttering, “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism,” salt crystals flaking onto my Malibu McDonald’s t-shirt.