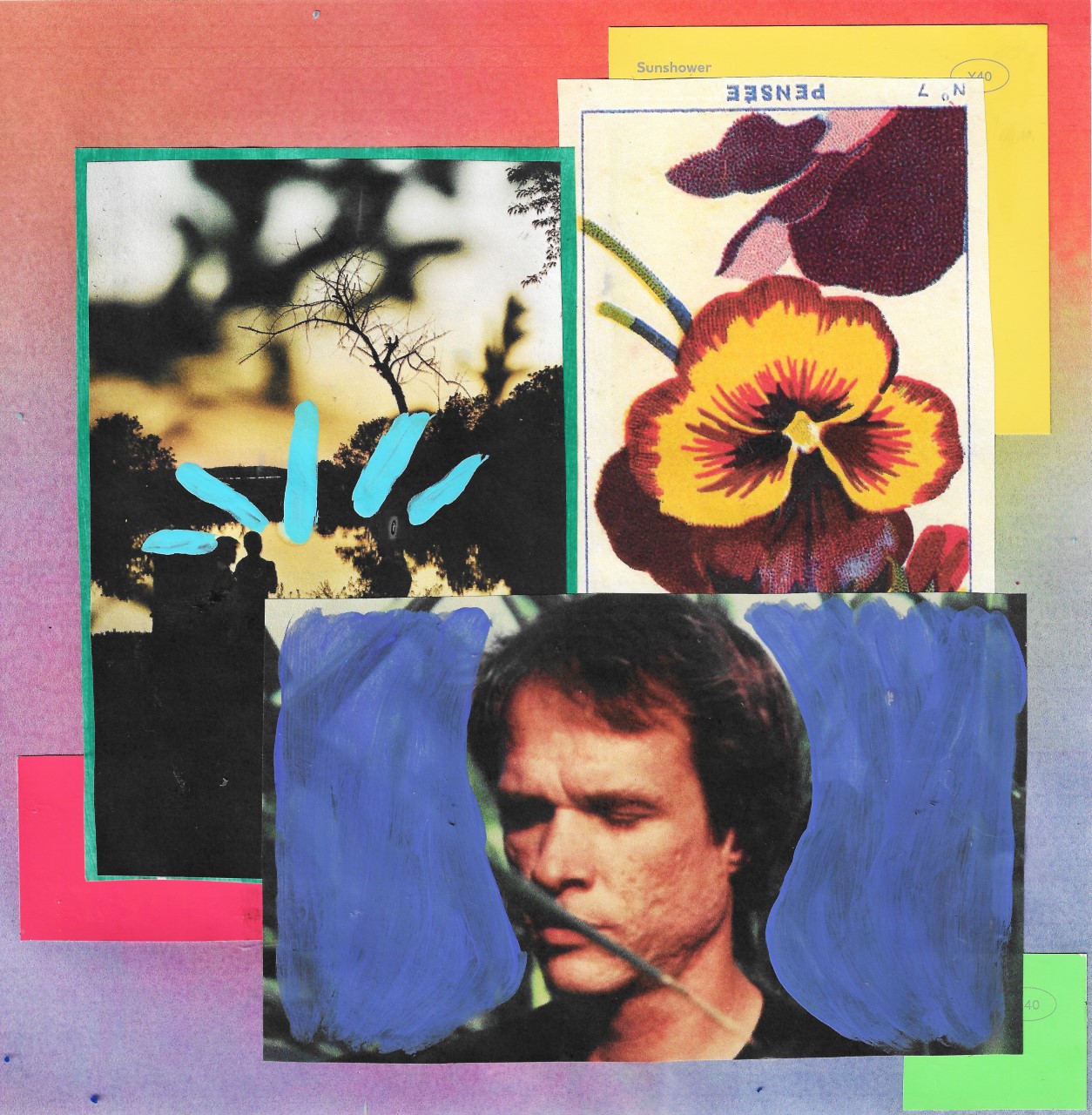

Art by Tina Tona and Phillip Pyle

Story by Phillip Pyle

Last week I drove to a nearby lake around dusk. It was a somber day, filled with relics of depression and monotony. I couldn’t even tell you what I had done that day, but I remember how I felt: nauseous, stuck, apathetic toward my environment. This is a common occurrence when I come home to Kansas on breaks. After a couple weeks of romanticized time spent with friends and family, the facade erodes, leaving behind a place that has been the epicenter of so many traumas, a multitude of experiences both formative and destructive.

As I was driving the serpentine backroads toward my destination, a brilliant light began to shine upon my surroundings. A golden earth arose from the nondescript landscape, absorbing the soybean and corn fields, the grazing cattle, and the gentle hills in its expansion as the hour approached sunset. And with this proliferation of warmth, of beatific light, my sadness, my indifference, my passivity toward my spatial and temporal circumstances; they all receded, leaving me in a joyous stupor.

The other day I watched the Andrei Tarkovsky film “Mirror” (1975). It being meditative on his own life and Soviet history as a whole, I was expecting an overwhelming nostalgia throughout the film’s backbone. Its poetic narrative is complemented by actual poems written and narrated by Andrei’s father, Arseny, which heightened the sentimentality and intimacy of it all. In one such poem, narrated during a scene of archival war footage, Arseny says, “There is only reality and light.”

Hearing this after my experience of stupefaction at the hands of a surreal Kansas sunset, I’ve begun to draw more parallels between my reality and light, substituting the latter with metaphorical lights. When I first got home from school in March and began quarantining, I fell in love with Kansas again. While a cliché, it seems to happen every time I take stock of the open sky, the rolling fields, the wind running its fingers through the wheat. However, as with most college students uprooted from their lives in March, I came home utterly depressed and detached from my reality. I began trying to find a tether – music, films, anything – to guide me through the liminal position I found myself in.

During the transition I began listening to the musician Arthur Russell for hours upon hours. I first discovered Russell a couple years ago when I became obsessive over music samples and found his song “Answers Me” from Kanye West’s “30 Hours.” Russell could have been a contemporary experimental pop artist for all I knew; my only point of reference being the album “World of Echo” (1986), an avant-garde record with heavy usage of echoing, distortion, and reverb added upon cello and other traditional instruments.

At home, I began to spend dedicated stretches of time listening to Russell’s discography. I was immediately drawn to his sound and simultaneously in awe of his genre-defying albums. His 2019 compilation album “Iowa Dream” was full of folk and country songs, poetic storytelling, and nostalgic meditations of his childhood. I began to research his life, wanting to know why I felt naturally attracted to his music and simple anecdotal lyricism.

Everything collapsed upon itself during a late night wikipedia dive. Russell was born and raised in the small rural town of Oskaloosa, Iowa in 1951. He was dead; he had died in 1992 at the age of 40. His cause of death was AIDS, his existence shattered by the failure of the U.S. to adequately address a disorder that has killed millions over the years, erasing a generation of queer people.

So I had fallen headfirst into Russell’s music, and I eventually knew why. I discovered the overlaps of our identities – us both being gay men from rural towns in flyover states. Though seemingly wonderful similarities, when the elements of his death are taken into account, his demise inflicted by AIDS, by a negligence to treat queer persons with human dignity, a sense of anger and abandonment began to shroud me. Even more, I soon came to learn during this period of manic research that the other artists who consoled me at home had also died early deaths. The music of Nick Drake, the melancholic British songwriter, and Elliott Smith, a Nebraska-born artist, began to take on a spectral meaning for me. Their relatability was thrown into relief, akin to them communicating with me beyond the grave, a subconscious affinity for those who have experienced similar bouts of self-alienation, depression, anxiety, and traumas associated with being gay in a world hostile toward queerness.

Although “World of Echo” was the only solo pop album released during Russell’s lifetime, his life’s work has been re-introduced by multiple posthumous albums, including “Calling out of Context” (2004) which features his most well-known song “That’s Us/Wild Combination” and the 2008 compilation album “Love is Overtaking Me,” which has served as a sort of reverie for me. His breadth of genius ranged from avant-garde, destructive disco to country-folk to spoken-word to poetic storytelling. His collaborations with Philip Glass and David Byrne and his longtime collaboration and romantic relationship with poet and artist Allen Ginsberg testify to his influence and the quiet grandeur he emitted through his own work and its reverberations in adjacent artists’ works.

Being home, I appreciate Russell’s tender and affectionate evocation of Midwestern landscapes. In the opening track of “Love is Overtaking Me,” “Close My Eyes,” he sings, “Will the corn be growing a little tonight, as I wait in the fields for you? Who knows what grows in the morning light, as we can feel the watery dew?” His pictorial lyricism has taught me to be more present in my own environments, to find beauty in what I take for granted, and in this case, to find the intricacies of the landscape I view with passivity. And just like the sun shone on the farmlands as I drove to the lake last week, Russell has shed a light on my own life. If there is only reality and light, as Tarkovsky expresses in “Mirror,” then my personhood, my experiences are reality, Russell’s music a beacon of illumination shed upon it.

There are many moments of my adolescence in Kansas clouded by guilt. Guilt for being gay, guilt for not telling others, guilt from hurting others by withholding my identity, guilt for a disconnect between my private and public self. But my time at home, with the help of Russell’s music, has broken that barrier down, that wall of previously insurmountable self-deprecation. What was once shame for my queerness and subsequent queer relationships has been replaced by a profound re-discovery. As I was re-enchanted by Kansas, I became appreciative of my upbringing and my unalterable characteristics.

However, with these moments of elation has also come an elegiac anxiety. If I cannot look around and see these figures, like Russell, who have so deeply affected me, alive today, where and whom do I turn to? The HIV/AIDS epidemic erased a generation that queer people would otherwise look up to, just as anyone looks to those with experience for guidance. And I can’t help but wonder what Russell’s legacy would be if the epidemic had been taken more seriously from its beginning. I was not taught about gay sex in sex-ed, let alone extensively taught HIV/AIDS and STD-preventative education. How many other queer children are growing up in rural, conservative environments, or for that matter, any environment unwelcoming to queerness, where they’re implicitly expected to repress themselves and not prepared to have safe sex? Everything I know about HIV/AIDS, STDs, and sex is self-taught, leaving a residual anxiety punctuating my every intimate moment with another.

And yet, I need not despair. As Russell sang, “I’m a wonder boy. I can’t do nothing.” I’m unsure what the next step is in the healing process, but I know I must not remain idle as queer and trans folks, particularly Black trans women, continue to be murdered, their voices suppressed and co-opted, their work erased and appropriated.