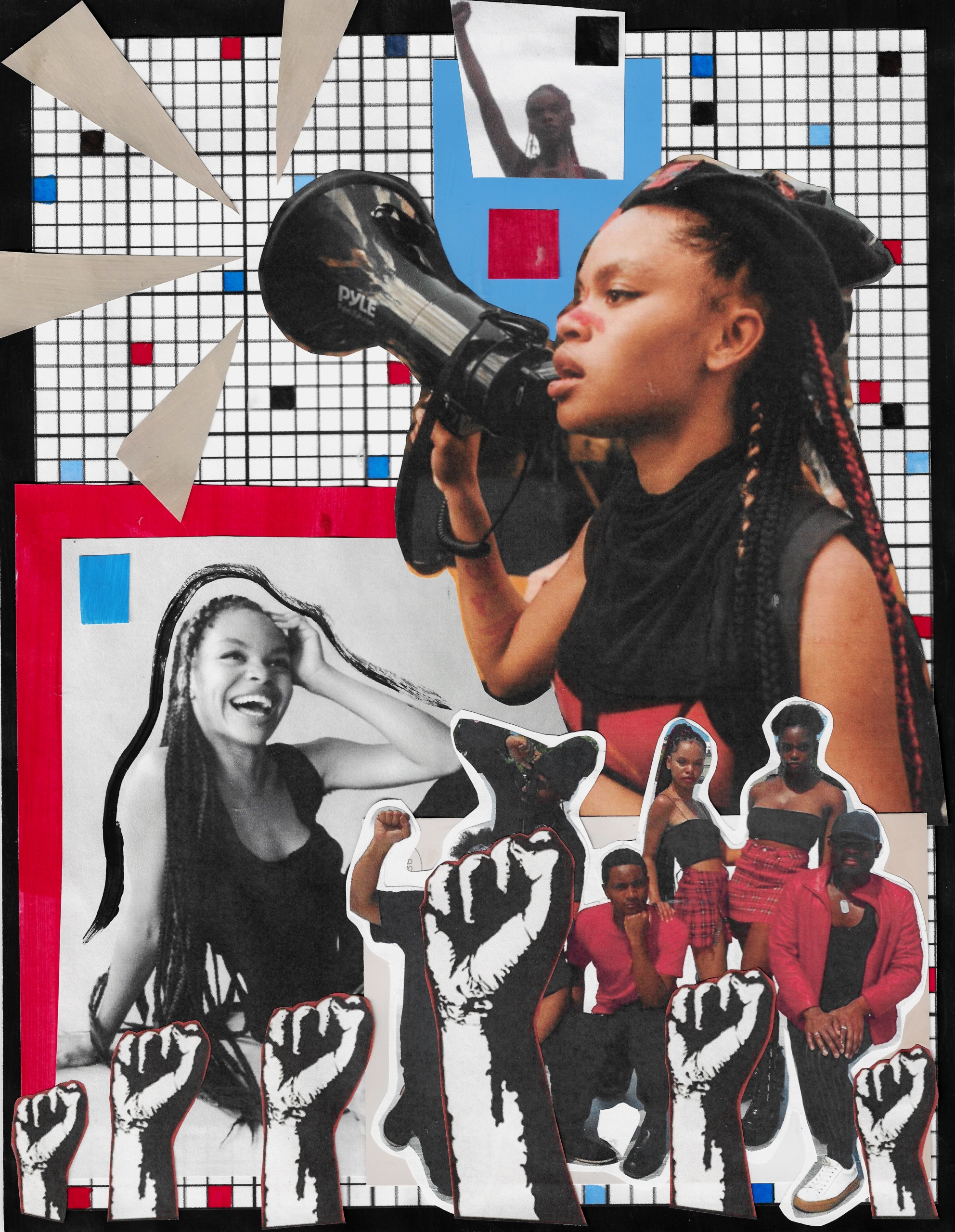

Art by Tina Tona

Story by Zoe Allen

Livia Rose Johnson is fighting for a better world for her brothers to grow up in. The 20 year-old, who hails from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, has found her voice in the wake of George Floyd’s televised execution that sparked a movement across the nation—and in New York City, one that is being led by Johnson.

She is a co-founder and leader of Warriors in the Garden, a New York City based advocacy collective “dedicated to peaceful protest for legislative change.” She’s been on the streets nearly every day for the last month, rallying thousands of New Yorkers, megaphone in hand. She is armed with the support of her fellow Warriors and city dwellers, as well as her altruistic desire to see her community thrive. She’s studying neuromarketing and neuroscience at Sarah Lawrence College, but plans to take next semester off to focus on her advocacy work and translating protests from IRL to URL. She’s also a model—and wants to use her voice to generate change in that industry as well.

I chatted with Livia on the phone on Sunday night after pestering her all weekend; as one can imagine, her schedule is packed. When we finally found a time to talk, chatting with Livia was like chatting with an old friend. From her home in Brooklyn and my home in Dallas, we discussed her recent modeling news, the origins of the name “Warriors in the Garden,” a certain hit 2000’s TV show set Down Under, as well as her perspective on the word “activism.”

ZA: Tell me a little bit about yourself. I know you as Livia Rose Johnson—a protestor, an activist and one of the co-founders and leaders of Warriors in the Garden. How would you describe who you are and the work you’re doing?

LRJ: I don’t consider myself an activist. I feel like activism is a dividing term. There are a lot of people who care as much, but because they have other main jobs, they don’t consider themselves activists. I want to take that term and I want to be like, “you should be a human.” I know some people would argue that humans are greedy, or humans are this other bad trait, but this should be the standard that humans are held to. That’s how I feel about it.

I’m a model, I also study neuromarketing and neuroscience at Sarah Lawrence. That’s what my main thing is about. I’m going to try to use neuromarketing and neuroscience to digitize protests while maintaining emotions.

ZA: I saw that you signed with Elite [Model Management] over the weekend, congratulations!

LRJ: They signed me as an activist. A model and an activist. I was just like, “you can sign me as whatever you want, but I don’t want to be called that.”

ZA: It’s funny, because I feel like I saw your Instagram post that was about how you don’t like being called an activist and then a day later it was the post when you announced you got signed by Elite. What was that process like, of getting signed to a modeling agency, in the midst of your work on the streets?

LRJ: After the “Vogue” interview happened, a lot of new shit came into play. Elite was interested in me since before quarantine, but they were going to wait a while and I feel like after they saw all the work I was doing…I’m on a board of Elite where I’m not in the normal model board, I’m in the creative team. So they signed me as an individual really, like I can model and can be an “activist.” It was interesting, really. I already have a mother agent, so I was used to it. I’ve been modeling for a while, so it just feels like the next step for me. I’m excited because I feel like this just gives me another platform that I’m able to utilize.

ZA: So even if it’s not exactly ideal to be called an activist, it is a huge platform that you’re going to have with them.

LRJ: Yeah, because you wanna know something? As a woman of color, but a light skin woman, I’m aware that I am usually more easily digested by the media. I’m aware of colorism, I’m part white, I’m one fourth Irish. I have some of that in me. I want to shed a light on that and allow that to be seen and challenging these people to be like, “yes, I want you to know why you chose me.” When I start modeling that’s going to be a really big thing.

ZA: I obviously want to chat about Warriors in the Garden. What is it and how was it started?

LRJ: So Warriors in the Garden is a collective of activists dedicated to peaceful protests for legislative change. We’re currently working on digitizing our protests to create informational content about Black culture, economics, legislation, socio economics and psychology because I believe that Black psychologies are a really big thing. We’re a group of 10 people. We’ve gathered up to 30,000 people, wait, 25,000 people, I’m not going to gas ourselves. We’ve had a lot of great people collaborate with us, like Danny [Cole] has been an incredible help. We’re meeting all these incredible people. Have you watched the show “H2O?” [Phoebe Tonkin] is now an affiliate of Warriors in the Garden now. We’re gonna be doing a video on allyism with her and we’re gonna be interviewing her and explaining to her how to be a genuine ally.

ZA: Oh my god, I know her. I don’t remember her character’s name, but I know her.

LRJ: It’s Cleo. Scroll through and watch our TikTok. We did a Cleo TikTok.

ZA: I’m looking. Okay, that’s iconic. I watched “H2O” but never all of it.

LRJ: I didn’t watch “H2O,” I watched “The Originals.”

ZA: I definitely recommend watching “H2O.” It’s mind numbing, but in a really good way. My last question about Warriors in the Garden—where did the name come from?

LRJ: So we had a group text and the original person, Joseph, made a code name called “Warriors in the Garden,” like how people make spy names. It was our code name and then the quote was “it’s better to be a warrior in the garden than a gardener in the war.” We really thought about it and I made the Instagram and just said fuck it, let’s call it Warriors in the Garden. That’s just who we are. It has a lot of different interpretations, but my personal interpretation that I like to use that not everyone in the group uses, but I do, is that our community is a garden that we need to nourish. We can fight for the rights that we need to fight for in the garden and treat our community like a garden. Personally, I understand the looting but I haven’t participated in it just because I think that we could use our time better. Looting, destruction, yeah, it’s getting the anger out and at the end of the day everyone needs to get their anger out in their own way, but also you need to realize that this is where we want our children to grow up equal.

ZA: It brings in the restorative focus.

LRJ: Yeah, exactly. It’s my home you know.

ZA: I love that. You’ve been attending and leading some protests in New York City nearly every day since the death of George Floyd a whole month ago, which is just hard to believe. Time has definitely moved in a really weird way for the last few months. I imagine you must be really physically exhausted and mentally drained. Could you speak to that and also about how you’re taking care of yourself right now?

LRJ: I did a little bit about that in “Vogue.” I talked about how I meditate every day, I have limits on my phone usually. I’ve actually taken a break from protesting because I broke down three protests in a row. The last protest I did, I posted a video of it. I think that the best thing is to understand what “me time” is. I’m literally in a relationship with Black Lives Matter and myself. You really have to prioritize what you need to prioritize. I think that everyone in this group has given up something. It’s just about balancing everything and being true to yourself, understanding that this is a fight, this is a war and this is not something that you can expect immediate outcomes from.

ZA: It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

LRJ: Exactly, exactly. It’s about pacing yourself. It’s not only just a physical marathon, it’s a psychological marathon, it’s an emotional marathon, it’s a socioeconomic marathon. It’s all of that.

ZA: I’ve been thinking about that in the context of social media content. I definitely think people are struggling with deciding about what they can and can’t post and I think it’s interesting because I feel like when people are telling others that they can only post about Black Lives Matter—and obviously everyone should be posting about it to a certain extent, to educate themselves and spread awareness—but when you say it’s the only thing you can post, it can inherently make it like a trend. But it needs to be about how to incorporate this movement into your normal flow of content.

LRJ: I agree so much. To go back to the “activist” thing, I felt like I was being really boxed into this activism role. I’m not saying that I have a problem with being politically correct, but I want to live my life.

ZA: I remember first hearing the phrase “Black Lives Matter” in 2014 in correlation with Ferguson. We were freshman in high school then. Very few people I knew at the time were discussing the events that were going on in Missouri in the way that people are discussing the events now. This time feels really, really different to me and it feels really multiethnic, multiracial and like a multigenerational movement. I think freshmen in high school do know what’s up this time. In your opinion, why now? What’s different about this moment than moments in the past?

LRJ: That’s a really amazing question. It’s a mix of things. One of the things is boom, coronavirus happened. Everyone’s on their phones, so everyone’s really able to put their lives aside for this. Two, even though it’s shitty to say, the police for some reason, will wait a month and then kill another black person. We didn’t have the fuel that we had with this one, where it was over 120 people in a month and high profile deaths. The police are so oppressive right now. I’ve been groped in the last month, I’ve been harassed by the police. They’re scrambling. I sometimes do feel bad for “innocent” cops who “want” to help, but end up being in these situations. Just quit your job.

ZA: Exactly. Besides seeing more police officers quit their jobs, what do you want to see come out of this movement?

LRJ: I want to defund the police. I want to reallocate the money into mental health resources for lower income POC communities, educational resources. I want to see nutrition, I want to see them take the money from policing and just allow it to go to these communities and have them flourish. These communities don’t need a billion dollars, but they do need people who believe in them and people who are willing to invest in them. With that money comes energy and time, because we’re in a capitalist society. That’s just how it goes. I really want to see a successful digitalization of this media. I really want to have the emotional correlations in protesting IRL be exactly the same as the emotional correlations in protesting digitally. I really want to have that power, because I feel like once we have that power, we can do anything we want.

ZA: I look forward to the day that I can feel the same things from my computer then I can, theoretically, from the ground. I wanted to circle back to your Instagram bio, your general sentiments about how you’re “not an activist,” you’re “just Black.” I wanted to hear you talk a little more about this statement and about what being Black, right now, means to you. You’re saying that you’re not an activist, you’re just black, but could you also see the flip of it, where if you’re Black, it’s an act of protest right now, too?

LRJ: Yeah, I just said that I think that every single Black person should be an activist and that there should be no difference between wanting rights for yourself and wanting a society where your little brothers can grow up in a way that’s not life threatening. I’m trying to secularize activism, normalize it and make it so it’s just like “I’m Black, therefore I need these rights.” And if you want to call me an activist for wanting basic human rights, you can, but that’s not the goal. I don’t want to be an activist, I’m not doing this for personal branding. I’m doing this because I have two little brothers, one that’s seven and one that’s one years-old and I refuse to let them live in a world where they could be stereotyped or oppressed because of the color of their skin. That’s what I’m doing it for. I don’t like the term activist because I think that there’s so many people that try to brand off of it and that’s disgusting.

ZA: I think your brothers are going to look back when they’re your age and know their sister did something really important. Is there anything that you would want our readers to know about you, Warriors in the Garden or Black Lives Matter in general? What word would you use instead of activist? Is there a specific word you like better than that?

LRJ: I never thought about that. I think it’s called an empath. Just somebody who cares. That’s really it. As an ending statement, I want to say to see the bigger picture and look for the longevity. Ignore the people who are looking at this as a trend. Don’t stop until they stop.