Story by Lily Goldberg

When weeks had passed without signs of slowing down, when college dorms were converted to hospital beds, when stores were shuttered and masks were made mandatory and when the fact that I wouldn’t see anyone but my immediate family for the foreseeable future began to set in, I had a sudden urge to learn yodeling. “Why not crochet?” you might ask innocently. “Or better yet, bake fresh sourdough?” Unfortunately, neither of those hobbies allows me the same excuse to scream my head off once a day without interrogation.

Not scream. Wail is more appropriate. Grief is, after all, what The New York Times called this feeling I have in an article asking us to please acknowledge our collective loss of normalcy lately for what it is: a loss. A living, breathing world has been ushered indoors and many among us have had to react so quickly to our new reality that we have barely processed the sudden death of our old one. And when something dies, it’s customary to wail for it. The Ancient Egyptians practiced the custom while mourning their pharaohs and the Scots-Gaelic keened over dead lads at Irish wakes. Lately, I’ve wanted to scream. Luckily, Fiona Apple did it for me.

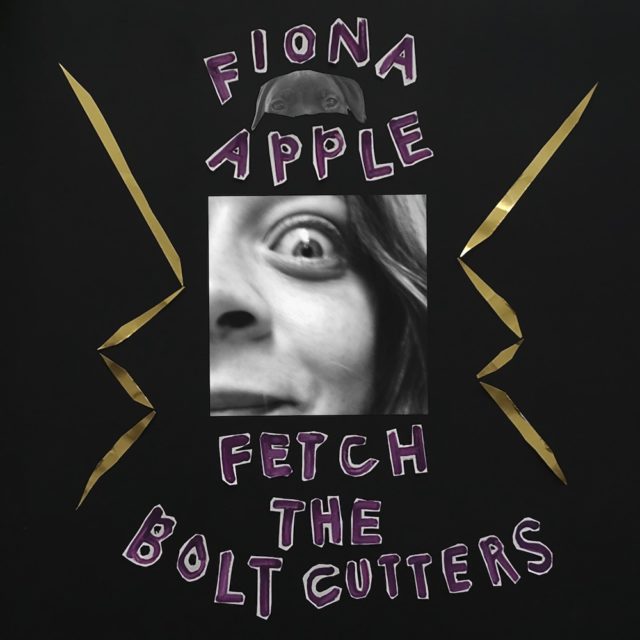

Fiona Apple’s newest album, “Fetch the Bolt Cutters,” is an extraordinary work in its own right. On Apple’s fifth studio album, she leans farther into the rhythmic speak-singing language she began to developed on her last album, “The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than The Driver Of The Screw, And Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do,” on tracks like “Left Alone” and “Hot Knife.” After listening through, you, like me, might feel surprised or even offended that Apple’s imagination and talent were ever spent on the conventional pop songwriting that appears on her first few albums. But perhaps even more extraordinary is how miraculously this album has arrived into—and how perfectly it reflects—the cultural moment into which it appears.

Nothing about the past few months has been conventional. Though whole cities have coordinated singing old favorites out the window and celebrities take to Twitter singing “Imagine,” this will hopefully be the extent of the conventional art made right now. Efforts like these might be comforting, but ultimately just attempt to replicate the creature comforts of social human life before it slowed to a staggering halt. “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is anything but conventional and in its embrace of the avant-garde, it simultaneously seems to mourn the normalcy we are leaving behind while striding pluckily into the new one.

“Fetch the Bolt Cutters,” after all, is an album born from and influenced by isolation. Apple has often been described as a recluse, due to the fact that she rarely made public appearances after her last album came out in 2012, instead remaining mostly inside her house in Venice Beach. In a recent New Yorker profile of Apple, writer Emily Nussbaum reports “the earliest glimmers of ‘Fetch the Bolt Cutters’ began in 2012, when Apple experimented with a concept album about her Venice Beach home, jokingly called “House Music”… Steinberg [Apple’s bassist] recalls “stomping on the walls, on the floor—playing her house.” Sometimes these rhythms feel like an angsty version of a marching band, like in “Relay.” But more often, these rhythms have a chantlike intensity and urgency made even greater, of course, by Apple’s insistent vocals.

Coupled together, the effect is almost primal, which is almost paradoxical considering this primal sound comes from “playing” Apple’s home, a decidedly manmade and contemporary structure. “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is such a unique album because it embraces this tension as a point of inquiry and exploration. By hitting her house repeatedly in rhythm, Apple might be rebelling against the structure of her house. But the pulse of the album appears as a byproduct of that rebellion—Apple is brilliantly repurposing her enclosure to make art out of it.

You might have sensed a metaphor was coming: it’s not just the enclosure of her house Apple is rebelling against and simultaneously repurposing. It’s the limitations and expectations imposed on women and more specifically on women artists. But without those expectations which defined Apple’s early career, she could not break free of them as radically and wildly and address them as honestly and angrily, as she does in “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.”

“Fetch the Bolt Cutters” certainly addresses these ideas, from the album’s very first lines. In “I Want You to Love Me,” Apple sings, “I’ve waited many years / Every print I left upon the track /Has led me here / And next year it’ll be clear / This was only leading me to that /And by that time I hope that /You love me.” But by the end of the song, Apple’s high pitched riffing gives way to convulsive vocal yelps reminiscent of Yoko Ono’s experimental “Voice Piece for Soprano.” It’s as if Apple has cracked under the pressure of wanting to be “loved,” but out of that fissure comes the more interesting work. The titular song on the album addresses this theme: Apple sings, “I grew up in the shoes they told me I could fill / Shoes that were not made for running up that hill /And I need to run up that hill, I need to run up that hill” before declaring “Fetch the bolt cutters / I’ve been in here too long.”

And once the bolt cutters are fetched, the album explodes. Directly after “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” comes “Under the Table,” where Apple declares, “Kick me under the table all you want / I won’t shut up, I won’t shut up.” Soon after on “Rack of His,” Apple delivers one of the most raw vocal performances on the album, snarling, “And meanwhile, I’m loving you so much “It’s the only reason I gave my time to you /And that’s it, that’s the kick in you giving up / ‘Cause you know you won’t like it, when there’s nothing to do.” Even for Apple, who often growls lyrics, this verse is startlingly fierce and feels like she is disrupting her own well-recorded and smoothed sound to provoke the limits of her own expression.

In a time where many celebrities are spreading messages of positivity and healing, it’s actually comforting to welcome the return of Apple’s angst and rage, which feels like the unexpressed subconscious of the world. It is also timely to hear an album which utilizes a house in creative ways for its rhythmic backbone, as many of us are stuck inside our own. Apple’s complicated rhythms, screams and whispers reflect back the confusion and surrealism of our current moment and allow us to reckon with our enclosure. Though the album was not written in response to the COVID-19 epidemic (Apple had been social distancing to work on it long before “social distancing” was even a turn of phrase) its lyrics speak to it preternaturally. The closing song of the album is a rhythmic chant of the words, “On I go, not toward or away / Up until now it was day, next day / Up until now in a rush to prove / But now I only move to move,” words which seem apt for our collective stasis. The rhythm of these words however, promise growth in some direction, regardless of whether that direction is known.

But as a writer of love songs, Apple also knows that before growth comes mourning. On the most conventionally composed song on the album, a slow jam called “Ladies,” Apple addresses the new girlfriend of her ex-boyfriend in what is hardly a conventional scenario—Apple invites the new girlfriend to raid her kitchen cupboards and bathroom cabinets. Justifying her lack of jealousy, Apple croons, “Nobody can replace anybody else / So it would be a shame to make it a competition / And no other love is like any other love / So it would be insane to make a comparison with you.” As people around the world struggle to replicate social rituals virtually, it is almost possible to hear this line as permission: instead of trying tirelessly to replicate a normalcy that can no longer be, perhaps we should allow ourselves to truly feel its difference. Or better yet, like Apple, we might allow ourselves to invite this new reality in. We might allow ourselves to make something of it.