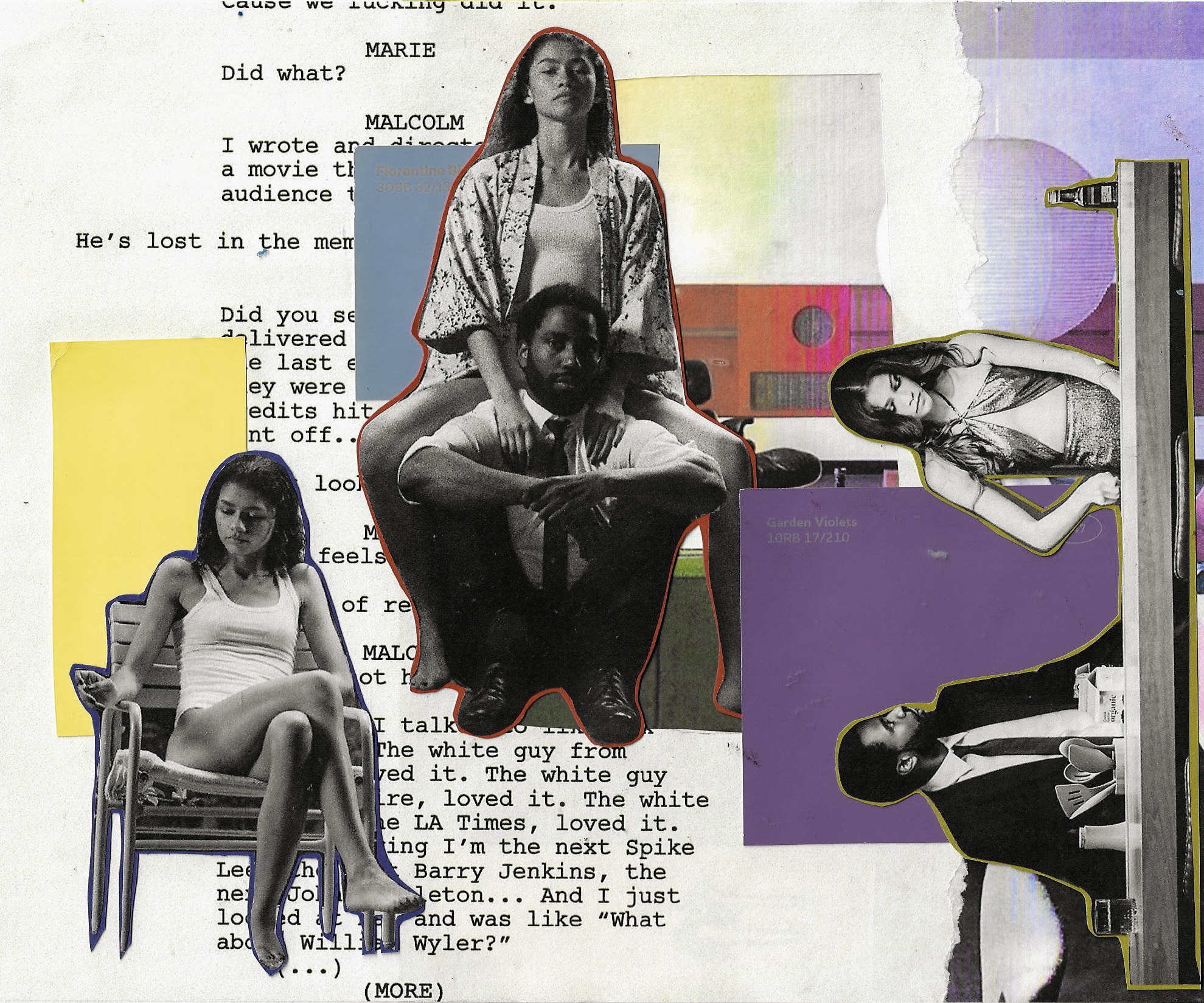

Art by Tina Tona

Story by Kimberlean Donis

“Malcolm & Marie” was meant to be a great addition to Netflix’s already poorly strewn together Black Lives Matter Collection. Instead, the film graced the streaming platform with a deeply immoral creative endeavor. Writer/director Sam Levinson worked to shoot the film during the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic in Carmel, California last summer. In just two weeks, a twenty person crew managed to beautifully shoot the scathing romance between “Euphoria” star Zendaya and breakout star John David Washington. The movie was written with this specific casting in mind, promising strong on-screen romance and a deeply personal performance as both actors also produced the film and had a large involvement in the final shaping of the movie.

Malcolm (Washington), is a filmmaker with big dreams haunted by the harsh reviews of previous critics. While he is riding the high of his recent film premiere, his girlfriend, Marie (Zendaya), a model struggling with past addictions, is less than pleased by her involvement in the film. Decked in an extravagant gown and sharp suit, the two arrive back home after a long night out experiencing two completely distinct waves of emotions. Malcolm is doing victory laps around the house to a particularly well curated playlist after a positive interaction with critics. While Marie is clearly sullen but still surprisingly supportive; working to cook a meal despite her anger.

Tensions between the two quickly begin to unfurl over a bowl of mac and cheese as the couple spend the night fighting after Malcolm forgets to thank Marie at the premiere for a movie for which she believes is based on her life story. And just as quickly as that issue arises, Malcolm’s initial joy quickly fades as he begins to nitpick at how his art may be interpreted, especially by white critics. These initial feelings should have been enough to create a beautifully nuanced piece of art. But here’s the thing, it does everything but that.

As striking as the cinematography is, “Malcolm & Marie” is an abysmal masterpiece. The scenes are raw and beautifully executed, and at times the relatability is terrifyingly accurate. But, this film is not a love story or even a story of love; rather an uncomfortable one hour and forty-six minute retelling of a larger issue of nepotistic Hollywood white artists using Black talent to push their creative licenses.

“Malcolm & Marie” was obviously intended to be a movie worth talking about. It stars two of the most acclaimed young actors in Hollywood and is written/directed by the creator of Euphoria who is also notably the child of Oscar-winning filmmaker Barry Levinson. The film was undeniably supposed to be a hot work of art for a starven group of Euphoria obsessed individuals—like myself. It takes a talk-heavy aim at Black love and the relationship artists have with their craft. So why does a topic so deeply complex have so little to say on-screen? The answer? Because it was written by a white man.

With so many themes to unpack my mind somehow continues to remain stuck on the reality that this is the work of Sam Levinson. How is someone who has never seen a Black couple talk behind closed doors going to write this film? How could a white creative just decide that his creative shortcomings from previous backlash deserve to be backed by a multi-million dollar studio? And I say this sarcastically, as it is not surprising really. This is usually how Hollywood works and more specifically how HBO operates—but this is just the first misfire in a never ending series of deeply questionable million dollar mistakes.

Perhaps the first and most glaring mistake of all is Levinson’s poor, misshapen take on Black creativity and the white gaze. Malcolm goes on a multitude of monologues throughout the movie, scared that his creative vision will quickly become limited by the critiques of white artists—artists much like Sam Levinson. “I want to be part of a larger conversation about filmmaking without always having white writers making it about race. I can already see the reviews, how this film is an acute study of the horrors of systemic racism in the healthcare industry. Instead of it being a commercial film about a drug-addicted girl trying to get her shit together. I mean these people are so fucking pedantic. We get it, you’re smart. We get it, you’re woke. We get it. We get it. We get it. Let us have some fucking fun.” The monologues are at best generic; clearly taking reused quips from well-known Black creators you could copy and paste right off of the internet. It becomes hard to tell what is more nauseating—a white man gleefully writing the n-word into his already tumultuous screenplay behind closed doors or the overwhelmingly distasteful hot takes on Blackness as it pertains to modern film discourse. For all the obsession Levinson has for Barry Jenkins and Spike Lee that he manages to constantly interweave into the script, he could have actually taken a hint or two from their work and realized that there is a strong, educated possibility that they would absolutely hate him and this movie.

Seemingly worse though is Levinson’s inability to grasp the complexity and trauma that comes with Marie’s experience. The film works hard to pin Marie as a stereotypical former drug addict capable of “more,” while ignoring the most glaring reality of all—Marie is a Black woman. Her issue is not a byproduct of just one distinct failure- a multitude of systems worked to break her and they will undoubtedly continue to fail her. And just one of those systems will always be Malcolm. If Levinson knew what was truly best—which he never will—he would have never put trauma porn on-screen and called it a true depiction of modern Black love. It is utterly ridiculous. Marie deserves better than Malcolm and his drawn out emotional abuse. Regardless of how compatible the two are on-screen and this was a pivotal plot line that was left virtually unexplored and it’s disturbing.

Malcolm is the unhinged artist and Marie is his emotionally abused muse. And somehow throughout all this chaos, Levinson’s whiteness has once again stolen the spotlight casting himself a “visionary filmmaker” using Black love to explore his already known lack of talent. In the vein of white masculinity, he simply took up too much space with little to no care for how his creativity really does not have to permeate every corner of Hollywood. In short, the film is maddening, there was so much room for potential with an all-star cast and fantastic crew; the writer just should have been Black.

“Malcolm & Marie” is undoubtedly an experiment of sorts, especially amid a pandemic. If anything, this project’s claim to being one of the earliest films to be produced during COVID should be the only thing to solidify it in history. It is deeply unfortunate though, this was supposed to be the Valentine’s Day movie to fulfill the mental gymnastics millions have experienced in the last few months. But now viewers are only left with a beautiful Black couple that could have been granted thematic nuances, and another glaringly uncomfortable example of the fact that nepotism can never equal true talent.